Tuesday, November 9, 2010

French Like Me (Part 9)

filed under: french like me 9.

9.

Against the gray clouds of an overcast sky, the columns and spire of the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette cathedral shot to the heavens like flora nourished by a glum god. With the end of summertime approaching, gloomy weather trudged on for days, rains bucketing down every now and then like sun showers in the tropics.

I sprinted up the métro station steps two at a time to meet Christine. I was late again, the second time this week. She sat listening to music on the granite steps of the church, waiting. Before I returned to Paris, Christine had removed her hair extension braids. She’d pressed her hair into a free-flowing Afro that I loved. An old denim jacket kept her warm, and the legs pouring out of her patterned Mexican skirt (the same cranberry shade as her lipstick) made me happy to be back. She removed her earphones, smiling as she saw me approach, and we kissed.

“Désolé,” I said, “I didn’t know the ninth arrondissement was this far from home. I thought Notre-Dame-de-Lorette was closer to the Notre Dame.”

“Miles. I told you yesterday, no, it was not. You take this.”

Christine handed me a métro map from her handbag, folded into eighths the size and shape of a credit card. I hated maps; she knew this. I didn’t want to look like a lost tourist, like an obvious American. The dreds grazing my shoulders already announced that I wasn’t from here. But cutting my locks was one thing, carrying a map around was another. I jut it inside the back pocket of my bluejeans. That night it went into the garbage.

“Merci Christine. Allons-y?” Chamoiseau finished, I was all into my idiot’s guide to learning French, trying to toss around as much of the native language as I could.

France gives five weeks of paid holidays every year, and Christine was in the middle of a few weeks off. In days she’d be leaving with Nadia for Corsica island, off the southeastern shore of France. I initiated her into some ghostbusting for the day, to help me dig up some spirits. My walking-tour book detailed the names, places and dates of black American expatriates, exactly where they impacted the city back in the day, and exactly when. We planned to walk through Saint-Georges and Montmartre to Pigalle (known as Pig Alley by black American soldiers back in WWII), the seedy neighborhood central to black expats from 1910 till around the Great Depression.

She took my hand to lift her up. Arm in arm, we turned the corner and walked down to the rue des Martyrs in search of a bank. The Crédit Agricole d’Ile-de-France on the corner was once Frisco’s, the popular 1920s jazz club of Jocelyn “Frisco” Bingham, according to the walking-tour book in my hand.

“You’re cold, chéri?”

I was freezing. I left Arcueil in a rush, not realizing my Nehru jacket matched my tan hemp jeans perfectly, and so I left it at the apartment. The jeans and jacket together looked like a Garanimals outfit, like I was auditioning for Boyz II Men. I chose to suffer for fashion instead.

“No, not at all,” I lied. “It’s better to look good than to feel good,” I said. It was a tired line, an eighties catchphrase from Saturday Night Live, but Christine cracked up, having never seen Saturday Night Live. Our relationship had become filled with moments just like this, where I said things I would never say to an American girl. Christine appreciated what made the joke funny fifteen years ago because her culture never ran the saying into the ground. Weather was harder to call now than in the springtime. The rest of the chilly afternoon, I pointed out the other unfortunates in T-shirts and claimed them as my brethren.

We turned another corner, crossing neighborhoods from Saint-Georges to Montmartre, and walked down the rue Clauzel a bit before reaching a familiar restaurant with a log cabin façade. The sign said Haynes American Restaurant but I had three different Paris guides that named it Haynes Grill, Haynes Restaurant, and just plain old Haynes. In June we approached it from a different direction and so we were both a bit surprised—like, how did it get here?

We turned another corner, crossing neighborhoods from Saint-Georges to Montmartre, and walked down the rue Clauzel a bit before reaching a familiar restaurant with a log cabin façade. The sign said Haynes American Restaurant but I had three different Paris guides that named it Haynes Grill, Haynes Restaurant, and just plain old Haynes. In June we approached it from a different direction and so we were both a bit surprised—like, how did it get here?

Haynes serves dry cornbread. The quality of the entrées at any soul-food restaurant in the world can be accurately predicted by the scrumptiousness of the cornbread appetizer. This is a no-brainer. Paris, of course, has no cornbread but Christine knew all about it from The Shark Bar on Amsterdam Ave, from the time she lived in New York. At Haynes we were not amused.

Months ago I’d taken Christine to dinner here, the very first soul-food spot in all of Europe, established in 1949 by Atlanta native Leroy Haynes. Photos from its heyday adorned the white stucco walls: black-and-white shots of Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Louis Armstrong, Richard Burton and Liz Taylor. A piano and sax duo immediately switched to some Miles Davis the minute we were seated. (My namesake followed me around often. Just last weekend his soundtrack to Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud trailed me through a Saint-Michel card shop.) The homely place felt like an old Southern restaurant that had fallen out of favor and relied strictly on its regulars. But Haynes had no competition. Soul food was only available there and over at Percy’s Place, a recent challenger in the sixteenth arrondissement rumored to be closing soon. Contenders like Chez Inez, Bojangles and Jezebel’s had long since shut down. I left feeling like Sean “Diddy” Combs could clean up opening a branch of his Justin’s restaurant franchise in Montmartre, another no-brainer.

We walked.

A small truck ambled down the rue Pigalle. We saw the same truck parked in front of a boulangerie five minutes ago and I wanted to walk back for a picture but I hadn’t mentioned it. The truck was midnight blue and bombed with graf, top to bottom. The main tag read POLO in sunset shades of orange and yellow, a nice piece. I noticed a lot of trucks bombed like this, apparently with permission, fruit and vegetable delivery trucks for Parisian groceries. The truck drove by and I instantly regretted not taking the photo again.

“Look! Yeah! She’s my sister,” I joked, pointing to a teenager racing by on roller skates. Not inline Rollerblades but skates: the old school, four-wheel, plastic kind. She wore a T-shirt with a toothy Japanimation character smiling widely on the front.

“Maybe she’ll lend you her skates,” Christine suggested. We laughed.

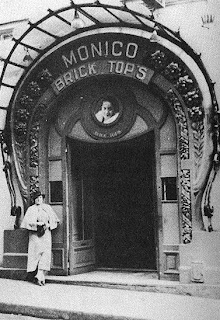

A neon green pharmacie sign blinked at the intersection of rue Pigalle and rue Fontaine. In 1929, fresh from singing jazz standards at Le Grand Duc (now a bistro called Miss China Lunch Box, up the block), Ada Louise Smith a.k.a. Bricktop capitalized on her popularity by opening up Bricktop’s here at 1 rue Fontaine. Now the place sold drugs. The Chicago-born Bricktop was a redheaded legend in her own time, and her club famously entertained the likes of boxer Jack Johnson and composer Cole Porter during the jazz age. I needed floss. Christine talked me out of it; dental floss costs too much at pharmacies, she said, better to try the supermarché.

A neon green pharmacie sign blinked at the intersection of rue Pigalle and rue Fontaine. In 1929, fresh from singing jazz standards at Le Grand Duc (now a bistro called Miss China Lunch Box, up the block), Ada Louise Smith a.k.a. Bricktop capitalized on her popularity by opening up Bricktop’s here at 1 rue Fontaine. Now the place sold drugs. The Chicago-born Bricktop was a redheaded legend in her own time, and her club famously entertained the likes of boxer Jack Johnson and composer Cole Porter during the jazz age. I needed floss. Christine talked me out of it; dental floss costs too much at pharmacies, she said, better to try the supermarché.

Many guitar stores and music shops populated the area, Marshall amps and mixing consoles in the windows. Music and sex continued to dominate Pigalle. A sleazy looking cabaret called Carrousel de Paris still listed its prix fixe menu in francs behind a gated window. (Euros replaced francs way back in 1999.) This was the former location of Chez Josephine, the nightclub of one of the most famous black Americans to storm the French capital. Josephine Baker—born Freda McDonald in St. Louis—first arrived in Paris as a La Revue Nègre dancer in September 1925 and sped to fame and fortune so fast that she opened her own club by December of the following year.

The red windmill of the Moulin Rouge twirled languidly in the near distance of the very next street, the boulevard de Clichy. Christine asked to deviate from the proscribed path of the walking-tour book and peep inside some of the sex shops.

“We always walk around Paris,” I said. “Today the whole point was to follow the—”

“D’accord, d’accord,” she said, rolling her eyes. What a universal sister gesture.

Reaching the boulevard de Clichy, we turned down the rue Blanche, back in the direction of Bricktop’s. We walked past the site of The Music Box (the old Chez Florence, which Bricktop renamed when she briefly took it over prior to premiering her own club) at 61 rue Blanche, made a left onto the rue Chaptal, and ended up right back at the drugstore that was Bricktop’s.

We held hands, hanging a right onto the rue Pigalle, and voilà, another graffiti truck. This one was actually a van parked at the intersection of rue La Bruyère, where a favorite Langston Hughes hangout called The Flea Pit used to stand. Two writers had worked the van over, MIEL and…TRORG? TROBG? TRORC? I couldn’t handle homeboy’s wildstyle technique, it was way over my head. The spray-paint colors were great. MIEL used tan block letters outlined in a sky blue over a burgundy backdrop. His throw-up covered the van door. TRORG was all over the place though, covering the body of the van in tan, burgundy and sky blue, but also aquamarine, lime green. The colors of his piece erupted violently from the ride. I reached inside my shoulder bag for the camera.

“Miel? What does this mean, Christine?” Click.

“Miel? What does this mean, Christine?” Click.

“Meal?”

“Oui, M-I-E-L.”

“Oh, miel.”

“That’s what I said!”

“Miel is honey.”

“Yeah? What about Trorc?” Click.

“Quoi?”

“What about Trobg?”

“That says THOR. We see this jazz history all afternoon and you want a picture of a truck?”

“This is a van.”

“Let’s go. Allons-y…” Click.

We walked.

“Christine, regard: a casino,” I said, pointing.

“This is not a casino. Not like you’re thinking.”

The Casino de Paris at 16 rue de Clichy was where jazz was introduced to Paris. Louis Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, so the story goes, performed here in 1918 and started the French love affair with the black American art form. Reading this in my walking-tour book made me think of the New York City Rap Tour of 1982, the first time hiphop crossed the ocean commanding Europeans to throw their hands in the air. I had free tickets to see Kelis at Le Bataclan for later in the week, the same sweaty venue where Afrika Bambaataa, the Rock Steady Crew and others brought hiphop to France for the first time.

Christine and I passed the place D’Estienne D’Orves and the majestic Saint-Trinité church talking about Yannick Noah, the former French tennis star. He cashed in on his sports fame to start a singing career. The whole thing sounded very John Tesh, the former Entertainment Tonight host who quit to pursue a schmaltzy new-age music career. A poster announced Yannick had sold out the Casino de Paris.

“My friends saw him two years ago at Bercy,” Christine said. “He’s good, really.”

We crossed the busy rue de Londres thoroughfare and she pointed to the nearby Théâtre Mogador.

“I performed there,” she said. “Remember my salsa tape?”

“Oui,” I said. “That’s the place? This is the next stop in the book.”

“After my first year learning salsa, we had a graduation ceremony at Théâtre Mogador.”

“I remember us watching that, that was here?”

“Oui. The class was excited to perform, like we were big time.”

“The book says Josephine Baker filmed a movie here, La Sirène des Tropiques.”

“I didn’t see that.”

“It was 1927.”

“Oh.”

I recognized the Galeries Lafayette mall in the distance, down about three streets. Police officers milled around a barricade blocking the rue de Provence, a side street. Flowers were attached to the metal bars of the barrier, dead petals strewn on the ground. Ribbons of blue, white and red were tied around thin beams in the fence. A notice handwritten in marker and taped to the steel railing read of someone named El Houcine, residency papers, walking a child to school and the healing of terrible injuries. I asked Christine to translate the rest. She stared silently upward. I followed her gaze across the rue de Provence, above the deserted Délices de Fleurs shop to the Paris Opéra hotel.

Traces of black ash haloed several windows, the clear evidence of a recent fire.

“You don’t know about this,” she said softly.

“There was a fire?”

“Twenty-four people died,” Christine says. “Eleven were only children, and all of the dead were African.”

“Really?”

“They were waiting for papers to live in France legally. Paris puts people in this situation into hotels that are very cheap, sometimes for many years, but you would not want to stay in places like this. They have mice and roaches, and many of the rooms, they have no windows. The fire started because the… How do you say, the man who watches for the—”

“The night watchman?”

“Oui, the watchman, he was arguing very loud with his girlfriend in the lobby, and there were candles on the floor. I think they were drunk. She went to the police last week to admit that maybe she knocked over some clothes on the candles during their argument, but she did not do this on purpose. She left after their fight. The candles may have burned the clothing and spread up the staircase, the only staircase in the hotel. This street is behind the Galeries Lafayette stores, which are very chic. But prostitutes work this street directly behind. A prostitute noticed the fire first. Africans were jumping from the windows. Some rooms had no windows.”

“God. The watchman is dead?”

“The watchman is in a coma.”

“That’s horrible.” I stared at the blackened hotel. Rudy Guiliani hadn’t been New York’s mayor for years, but my first thought was to wonder what his typically callous reaction might’ve been to homeless African immigrants burning in a death trap Manhattan hotel.